Last time, we journeyed upstream to my boyhood home — Rochester, New York.

Like every child, I believed that my hometown was the best city on earth. Many years later, I still believe I was fortunate to have grown up there, but I now have a more nuanced view. In the 1970s, it was a great town for a little, white boy whose dad was an optical engineer at Kodak. If you were a poor black child growing up in the High Falls area of the Genesee River, your life experience was quite different.

Like every child, I believed that my hometown was the best city on earth. Many years later, I still believe I was fortunate to have grown up there, but I now have a more nuanced view. In the 1970s, it was a great town for a little, white boy whose dad was an optical engineer at Kodak. If you were a poor black child growing up in the High Falls area of the Genesee River, your life experience was quite different.

Though Rochester’s Race Riot of 1964 happened just prior to my family moving there, I did not begin unpacking those events until very recently. Until now I had never asked the question, “What caused the 1964 Race Riot? I assumed I knew. Unlearning what we thought we knew is always the hardest part.

In the 1960s, our family physician, Dr. “C”, had expressed a theory to our family that reflected the views of most white Rochesterians at the time: “Southern whites give black families one-way bus tickets to northern cities to get rid of them, their social problems, and to put them on the northern welfare rolls.” The unstated fear was that the “riffraff” that brought unrest and protests to Selma, Birmingham, and Montgomery would bring that upheaval to our town.

As a 10-year-old boy whose family fled to the all-white suburb of Greece, New York, I was oblivious to the influx of black folks to Rochester. As I grew older, I unconsciously adopted aspects of Dr. “C’s” narrative. Was he right?

The limitation to Dr. “C’s” perspective is that he never went upstream. He never paused to ask, “why are things like this?” He didn’t feel he needed to. He felt that he already knew. Since he was a respected physician and a school board member, didn’t feel the need to befriend any local black civic leaders or to study the living conditions of black families who lived in Rochester. Because he didn’t go upstream, he mistook the symptoms he saw during the six o’clock news for being the actual problems. Ironically, Dr. “C” misdiagnosed the situation because he never saw or talked to the patient.

Dr. “C” was right about one thing. Blacks were relocating to the north in droves. Six million moved from the south to the north between 1916 – 1970. This is known as the Great Migration. Growing up in the 70’s, I was entirely unaware of this event. I didn’t come across the phrase the “Great Migration” until I began studying our country’s racial history.

The Great Migration came in two waves: 1916 – 1920 and 1940 – 1970. Prior to the Great Migration, nearly 90% of all blacks lived in rural southeastern United States: 75% on farms. By 1970, 90% of all blacks lived in cities, with 50% of them living in northern cities.

The first half of the First Great Migration was from 1916 to 1920. World War I triggered a tremendous labor shortage in the north. Foreign immigration slowed at a time when demand for unskilled laborers skyrocketed. Corporations sent recruiters to black communities in the south to bring black workers up north to ease the labor shortage. Businesses provided train tickets and low-cost housing to entice black laborers. So blacks were indeed provided one-way tickets; not by southerners, but instead by northern business recruiters. Dr. “C” was half right — but wrong on the most important part.

In Dr. “C’s” defense, there was a national news story that came out in 1962 about the “Reverse Freedom Ride.” George Singlemann, a member of the New Orleans Greater Citizens Council, devised a plan to purchase bus tickets for southern blacks and send them to northern cities. An estimated 200 bus tickets were purchased and given to black individuals and families. About half of those black families were sent to Hyannis, Massachusetts, the hometown of President John Kennedy. Many of those sent Hyannis and were told that there were jobs waiting for them, along with free housing, and that the Kennedy family would be waiting to greet them when they got off the bus. None of this was true. They were sent up north, penniless, with no jobs, and no place to stay. The NAACP and other black organizations worked hard to pick up the pieces for many of these deceived individuals, helping them find temporary housing and employment.

This publicity stunt obviously remained in the memory of Dr. “C” and doubtlessly many other northern whites. It likely led many to the mistaken conclusion that the entire Great Migration of was the brainchild of clever southern whites. This racist banter was passed on as gospel among the northerners who opposed Civil Rights legislation and resented blacks for relocating to their cities.

Regardless, the first black migration had very little impact on Rochester. Second Great Migration, however, hit Rochester like a flood. As a city, Rochester reached its population apex in 1950, with 330,000 people, of which only 7,800, or about 2.3%, were black. By 1960, Rochester’s black population would triple to 23,500. A total of 40,000 blacks migrated to Rochester between1950 to 1970.

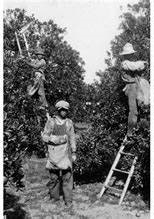

Seasonal migration to Rochester began in the 1930s. In Sanford, Florida, blacks primarily worked picking oranges from December to May. Year-round work was scarce in Sanford. In upstate New York, farmers were having difficulty finding laborers for the fall harvest. In 1929, John Gibson found work at the Fish brother’s packing plant in Sodus, NY, about 30 miles east of Rochester. That fall, he worked in the Fish brothers’ vegetable farm and orchard. In 1931, they hired him to bring 25 workers from Sanford, Florida, to work in their packing plant in the summer and their vegetable fields and orchards in the fall. By the late 1930’s, 75 men seasonally migrated from Sanford to Sodus every year. The blacks that commuted were eventually able to buy their own cars and homes. As a result of this relationship, more black families moved to Rochester from Sanford, Florida, than in other communities in the south. Other areas that black families migrated to Rochester from included other communities across Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Seasonal migration to Rochester began in the 1930s. In Sanford, Florida, blacks primarily worked picking oranges from December to May. Year-round work was scarce in Sanford. In upstate New York, farmers were having difficulty finding laborers for the fall harvest. In 1929, John Gibson found work at the Fish brother’s packing plant in Sodus, NY, about 30 miles east of Rochester. That fall, he worked in the Fish brothers’ vegetable farm and orchard. In 1931, they hired him to bring 25 workers from Sanford, Florida, to work in their packing plant in the summer and their vegetable fields and orchards in the fall. By the late 1930’s, 75 men seasonally migrated from Sanford to Sodus every year. The blacks that commuted were eventually able to buy their own cars and homes. As a result of this relationship, more black families moved to Rochester from Sanford, Florida, than in other communities in the south. Other areas that black families migrated to Rochester from included other communities across Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

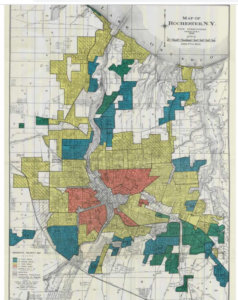

As the Second Great Migration began in earnest in Rochester, the question arises, where did all these new families live?

In 1934, the National Housing Act created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to promote home ownership by federally backing individual mortgages and reducing the initial down payments to 10%. Prior to FHA mortgages, a 30 to 50% down payment was required to secure a mortgage.

The FHA, however, would not back what it considered a risky mortgage. In 1935, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) examined 239 cities and created “residential security maps” to indicate the risk level associated with each neighborhood. There were four levels of risk, “A” through “D.” On these maps, the newest areas — those considered most desirable for lending purposes — were outlined in green and known as “Type A”. “Type D” neighborhoods were outlined in red and considered too risky for an FHA-guaranteed mortgage. These redlined neighborhoods were older neighborhoods and primarily black.

From 1935 – 1970, 35 million families purchased their homes through either FHA or Veteran’s Administration (VA) mortgages. Unfortunately, FHA loans expressly forbade lending to a black person moving into a white neighborhood. Eighty-five percent of all black neighborhoods were redlined. As a result, only 2% of black families benefitted from FHA and VA loans. According to a New York State report published in 1958, not one black family received an FHA or VA mortgage to purchase a home in any Rochester suburb. Prior to the 1968 Fair Housing Act, most black families missed out on the benefits of wealth accumulation through home ownership. As a result, the racial wealth gap in our country ballooned. In 2016, the average black family had $17,000 of accumulated wealth, while the average white family had $171,000 of accumulated wealth.

From 1964 – 68, race riots like this one broke out all across the country. Several studies have identified some common underlying causes. These studies found that bad policing practices, a flawed justice system, inadequate housing, and high unemployment were closely correlated to the race riots in the 1960’s. Rochester’s story would seem to be a case in point. Unfortunately, our nation’s race riots were not viewed this way by many white folks at that time.

From 1964 – 68, race riots like this one broke out all across the country. Several studies have identified some common underlying causes. These studies found that bad policing practices, a flawed justice system, inadequate housing, and high unemployment were closely correlated to the race riots in the 1960’s. Rochester’s story would seem to be a case in point. Unfortunately, our nation’s race riots were not viewed this way by many white folks at that time.

Dr. “C” would see the riots as proving his point that the black community was full of “hooligans and riff-raff looking to cause trouble.” Yet he was entirely unaware of the struggles of the typical black family living in Rochester. His perspective was based on his experience and how these events affected him and his family. He never paused to consider the antecedent causes. He was like a sports referee throwing a flag on the retaliatory punch, while missing the initial blow that started the entire incident.

Because of the segregated nature of our society, Dr. “C” was totally cutoff from the difficulties faced by those who lived in the High Falls neighborhoods. From his perspective, blacks didn’t want to work. They preferred welfare checks. For blacks, however, their experience was that no one was willing to hire them. He was unaware that blacks were forced to live in overcrowded housing that was substandard long before they ever arrived. It is easy to understand how these two very different perspectives drifted towards antagonism. The only way forward, to understanding and healing, is for everyone, the black community as well as the white community, to go upstream.

Going up stream is not an intellectual pursuit. You won’t find your answer in some book. It is a journey of curiosity fueled by love. It is based on an understanding that God has designed us to be interconnected and interdependent. We are to rejoice with those who rejoice; and we weep with those who weep. We must realize that when one person hurts, eventually we all will hurt.

When we understand our interconnectedness, then we go upstream to stop the harms that our friends are experiencing. At least, that is why I am going upstream. My friends have tremendous struggles, and I am determined to find out why. I am slowly gaining a better understanding, learning how to listen and love those who are not like me, and have gained many new friends in the process. Although it has been a rewarding journey, it has been arduous and slow; primarily because for me, unlearning is the hardest part.