The Initial Reason We Journey Upstream Is To Get A Better Understanding Of Our World.

The main benefit, however, is that we gain a better understanding of ourselves.

As the 1980s arrived, my time in Rochester was coming to a close. After graduating from Greece Athena High School, I headed south to Central Bible College in Springfield, Missouri. Springfield is the Mecca of the Assemblies of God (AG). The International Headquarters is there along with the Gospel Publishing House, which publishes all the denominational materials including the weekly denominational magazine, “The Pentecostal Evangel.” Springfield was also home to three AG colleges: Central Bible College (CBC), Evangel College (now Evangel University) and the AG Seminary.

As the 1980s arrived, my time in Rochester was coming to a close. After graduating from Greece Athena High School, I headed south to Central Bible College in Springfield, Missouri. Springfield is the Mecca of the Assemblies of God (AG). The International Headquarters is there along with the Gospel Publishing House, which publishes all the denominational materials including the weekly denominational magazine, “The Pentecostal Evangel.” Springfield was also home to three AG colleges: Central Bible College (CBC), Evangel College (now Evangel University) and the AG Seminary.

So “south” I went. At CBC, I was introduced to strange new foods: biscuits and gravy, cornbread, okra, and grits. The variety of southern accents surprised me. The accents of students from Arkansas, Alabama, and Kentucky were the most striking to me. One freshman from Alabama had such a thick accent that my Pennsylvania roommate bestowed upon him the sobriquet of “Gomer” (an allusion to the TV character Gomer Pyle from the Andy Griffith Show). My friends from Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana liked this playfully pejorative nickname, so it stuck. Eventually the entire campus called him “Gomer” –– well, at least some of my Northern friends.

Springfield was a very different place for this Upstate New Yorker. At the time, I couldn’t imagine any place in America further south. Now, I might not have actually been in the south, but for a young man from Rochester with a strong regional bias, it sure felt “south” to me. Feeling homesick and displaced, I sought out friends. Although it didn’t dawn on me at the time, nearly all my new friends were northerners.

Unfortunately, my northern friends shared my strong regional bias. One not-so-subtle hint of this was calling a classmate, “Gomer.”

I recall a revealing conversation with a player from our intramural softball team. He was from Kentucky. After the game, he reminded the rest of the team that Kentucky was a border state. It is merely separated from Ohio by the Ohio river. Kentucky wasn’t very far south. In fact, he argued, it was practically a northern state. Admittedly, I had never pondered Kentucky’s geography before that moment.

But the real issue wasn’t Kentucky’s proximity to Ohio. The real question is why would he feel compelled to bring up that subject in the first place? We might not have called him, Gomer, but he must have sensed our unconscious biases. We had stereotypical views about southerners that had been informed by TV: The Beverly Hillbillies, The Dukes of Hazard, and the Andy Griffith Show. Those feelings about the south were bound to come out sideways in our conversations. We weren’t intentionally being malicious, but our biased judgments were palpable to our friend from Kentucky.

Human beings are tribal: we gather in groups. Tribes provide us a sense of safety, security, and a sense of belonging. Sociologists call this “bonding capital.”

The unfortunate byproduct of tribalism is that for every “us” there’s a “them.” The things which divide tribes from each other are known as boundary markers. They could be things such as a river or regional accents. They also could also be ethnic, political, or religious ideologies. Tribal boundary markers are binary: you are either on one side or the other. There is no in between, you’re either in or you’re out. They also can generate conflict.

For example, some hot button tribal boundaries are abortion, the 2nd Amendment, and segregation. For each topic, you either support it or oppose it. You’re either “us” or “them.” Finding common ground, exploring nuances, and understanding other perspectives are not tribal values. Orthodoxy is. Each tribe believes it is right. Since the boundary marker is the organizing principle of the tribe, losing this boundary battle is an existential threat to the tribe. Respect, compassion, and curiosity towards other tribes is virtually impossible in the midst of a tribal boundary war.

My friends and I weren’t aware that we had created a northern tribe; we just felt comfortable with each other. I had more in common with someone from Pennsylvania or Ohio, than I did with someone from Alabama or Kentucky. There was nothing nefarious about that. Our friendships were building social capital. We weren’t actively thinking of ways to keep others out. Our unconscious tribal boundary marker did that for us.

Our friend from Kentucky realized he was on the outside. He wasn’t declaring war on our boundary marker. Instead, his geography lesson was his way of asking to be included in our tribe. He sensed our subtle condescension. He wanted to straddle the Ohio River and be included in our group. He didn’t want to leave his group, he wanted to belong to both groups. I don’t remember what our response was that day, but I imagine that we sarcastically thanked him for the “geography lesson,” laughed and walked away. Our boundary marker remained intact.

Although my move from Rochester to Springfield was a big adjustment for me, there was one thing that remained unchanged. Just like my hometown, CBC was a white space. There were virtually no black students on campus. Out of 1,000 students, there were about two dozen students of color. There might have been a dozen Hispanic students, six or seven black students, and six or seven students representing other ethnicities. Our campus was ninety-eight percent white. All the professors were white, save our speech instructor who happened to be the adoptive Egyptian son of a famous AG Missionary couple.

The homogenous whiteness of the Assemblies of God is rather surprising considering the denomination’s roots.

William Seymour

The AG was birthed out of the Pentecostal movement that launched from the Azusa Street Revival (1906 – 1909) in Los Angeles. William Seymour, a black pastor, was a leading figure of the revival. William Seymour was born in Centerville, Louisiana, to former slaves, Simon and Phillis Seymour, just after the Civil War ended.

In 1905, Seymour wanted to attend Charles Parham’s Bible school in Houston, Texas. As a segregationist, Parham was unwilling to allow Seymour in his classroom, but he did allow him to listen to his lectures in the hallway. Parham would keep the door ajar so William Seymour could hear the lesson. Being a moderate segregationist, Parham would preach to black congregations. He did not, however, allow Seymour to preach to white congregations. Parham had hoped that Seymour would share his Pentecostal message to black parishioners throughout Houston.

Instead, in 1906, Seymour moved to Los Angeles and he began preaching in an abandoned AME church on Azusa Street. When the revival started, Seymour’s congregation was mostly black, but over time, many ethnic groups began worshiping together, including whites. Unlike his mentor, Seymour did not permit any form of racial discrimination.

At a time when racial segregation was the norm, the Azusa Street Revival became renowned for breaking down racial barriers: warring tribes were coming together. Derided groups, such as the Mexicans and the Chinese immigrants, worshiped alongside black people as well as poor white Southerners. The Azusa Street Revival spread from coast to coast.

As the revival grew, so did its controversy. Many church leaders didn’t approve of the emotional nature of the worship services. For most, however, the most troubling aspect of the revival was the integration of the races. Even Seymour’s mentor, Charles Parham, vigorously disapproved. For most southern white Christians, skin color was a hard boundary line never to be crossed.

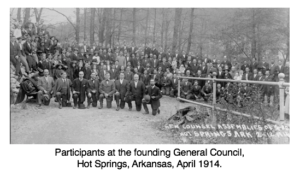

In 1914, a group of approximately 300 ministers met in Hot Springs, Arkansas to form a new Pentecostal denomination: The Assemblies of God (AG). Prior to the formation of the AG, a large number of white Pentecostal ministers were ordained by the Church of God in Christ (COGIC) a black Pentecostal denomination. Many of the ministers who converged in Hot Springs had been ordained by Charles H. Mason, the founder and first bishop of COGIC. Mason made a determined effort to ensure that COGIC was an integrated denomination. He ordained hundreds of white clergymen as a big part of his integrated vision — 300 white ministers in 1910 alone. Unfortunately, those whom he ordained did not share this vision.

In 1914, a group of approximately 300 ministers met in Hot Springs, Arkansas to form a new Pentecostal denomination: The Assemblies of God (AG). Prior to the formation of the AG, a large number of white Pentecostal ministers were ordained by the Church of God in Christ (COGIC) a black Pentecostal denomination. Many of the ministers who converged in Hot Springs had been ordained by Charles H. Mason, the founder and first bishop of COGIC. Mason made a determined effort to ensure that COGIC was an integrated denomination. He ordained hundreds of white clergymen as a big part of his integrated vision — 300 white ministers in 1910 alone. Unfortunately, those whom he ordained did not share this vision.

Between 1919 and 1939, only a handful of black ministers had been ordained, apparently, by mistake. On July 13th, 1939, AG General Secretary J. Roswell Flower wrote a letter to address an issue that had been brewing in the Eastern District of the AG. The district had ordained “Brother Ellison,” a black pastor from New York City. The Eastern District now requested that the national leadership revoke Ellison’s ordination, because at the time of his ordination, they did not realize that he was “colored.”

Robert Brown, the pastor of the prestigious Glad Tidings Tabernacle in New York City who had endorsed the first black AG minister for ordination, had a reputation for recommending black ministers for ordination without disclosing their race. He understood that the AG had unofficially adopted de facto segregation and he sought to flout it. In Flower’s letter, he stated, “It seems strange that the only ministers in our fellowship at any time during the past twenty years who are colored have been brought in through Brother Brown’s influence.” Flowers continued, “To my knowledge we have never had any colored ministers in our fellowship except in the Eastern District.” Apparently, Flowers saw ordaining a black minister as a grave mistake: it violated a tribal boundary. He set out to ensure that this would never happen again.

Robert Brown, the pastor of the prestigious Glad Tidings Tabernacle in New York City who had endorsed the first black AG minister for ordination, had a reputation for recommending black ministers for ordination without disclosing their race. He understood that the AG had unofficially adopted de facto segregation and he sought to flout it. In Flower’s letter, he stated, “It seems strange that the only ministers in our fellowship at any time during the past twenty years who are colored have been brought in through Brother Brown’s influence.” Flowers continued, “To my knowledge we have never had any colored ministers in our fellowship except in the Eastern District.” Apparently, Flowers saw ordaining a black minister as a grave mistake: it violated a tribal boundary. He set out to ensure that this would never happen again.

Events moved quickly as Ellison’s ordination and the larger issue of racial segregation took center stage. The General Presbytery met in September of 1939 to deal with the issue. At that time, the AG revoked Ellison’s ordination and made it the official policy not to ordain black ministers in the future. They would refer them to other black Pentecostal denominations, such as COGIC. The official record stated:

“It was finally moved and carried that the General Presbyters express disapproval of the ordaining of colored men to the ministry and recommend that when those of the colored race apply for ministerial recognition, license to preach only be granted to them with instructions that they operate within the bounds of the district in which they are licensed, and if they desire ordination, refer them to the colored organizations.”

Now the Assemblies of God’s position on race was officially codified. The tribal boundary marker was firmly established. This continued to be the AG’s official position until 1959.

To be clear, unlike many other denominations, the AG never advocated for Jim Crow or for Segregation. In fact, there was debate almost every year about what to do about the “colored” question. Some pointed out the inconsistency of sending missionaries to Africa, but not sending missionaries to minister to “colored” people in our own inner cities. There was discussion of forming a separate “Colored” wing of the AG. Yet, there was not the political will to initiate significant changes.

Apparently, the top leadership did the calculus and decided that addressing this “hot button” issue of segregation would have fractured the denomination. Segregation was a cultural norm that was deeply embedded in the hearts of many southern parishioners. Denominational change would not have equated to change at the local level. It would have led to a mass exodus.

Between a rock and a hard place, the leadership did nothing, until Thomas Zimmerman became the General Superintendent of the Assemblies of God in 1959. He was moved by what he saw during the Civil Rights movement and recognized that there were racial inequities within the AG. He sought to rectify things. He didn’t have to wait long for his opportunity.

In 1960, an incident with a man named Robert Harrison surfaced. Its resolution was the watershed event that officially ended the AG’s policy of clergy segregation.

Harrison had applied for ordination through the Northern California/Nevada District Council in 1960. In 1950, he had graduated from Glad Tidings Bible Institute in Santa Cruz, California to prepare for the ministry. The school was owned and operated by the Northern California/Nevada District of the Assemblies of God. The fact that he could attend their school but be denied ordination was a situation fraught with legal peril. There was never a question about his character or his ability. The reason Harrison could not be ordained was because he was black.

Thomas Zimmerman brought the issue to the General Presbytery in 1961. After deliberation, they determined that each district could ordain any minister they wished, regardless of race. Harrison was ordained the following year, making the AG one of the last evangelical denominations to integrate its clergy. Thomas Zimmerman even invited Harrison to speak to the 1967 General Council. He believed that the church was now ready to hear an important message on race.

Thomas Zimmerman brought the issue to the General Presbytery in 1961. After deliberation, they determined that each district could ordain any minister they wished, regardless of race. Harrison was ordained the following year, making the AG one of the last evangelical denominations to integrate its clergy. Thomas Zimmerman even invited Harrison to speak to the 1967 General Council. He believed that the church was now ready to hear an important message on race.

Harrison was not bashful in addressing the issue of racism in his message:

“A child of God cannot say he will live in fellowship with all people provided they have the right skin coloring . . . It is my conviction that the true Church cannot afford to ignore or remain neutral on such an issue which obviously defies the very heart of the Christian faith—love . . . I believe love . . . entails not only being friendly to people of every race, but also showing concern about the welfare of all people in one’s society.”

The efforts continued through the next two General Superintendents. To address some of the continuing racial disparities in the AG, in 1999, the General Council voted to expand the executive leadership by creating a position dedicated to ethnic representation. Spencer Jones, pastor of Southside Tabernacle in Chicago, was elected as the first representative from the ethnic fellowships. The previous year, Spencer Jones had publicly questioned the AG’s commitment to racial reconciliation. He stated that the track had been laid for reconciliation, but up to that point, the AG had gone nowhere. To the AG’s credit, Jones’ criticism likely led the AG leadership to create this new position, choosing him to fill it.

Later in his life, Jones had said that he appreciated all the AG had done for him, yet, “… in the Assemblies of God I’ve faced a lot of racism and prejudice.” I would imagine that most of his white clergy peers would have been surprised to hear that. They still would have been blind to their own biases.

Deep rooted change happens slowly. It doesn’t happen merely by making a policy decision. By the time I attended CBC, the college was less than 2% minority, 20 years after the policy change. Nearly 40 years later, an AG leader reports that racist attitudes could still be detected within the denomination. However, things have begun to change. As of 2016, the AG reports that 10% of its membership is now black. It didn’t happen overnight. It took 60 years of a lot of hard work.

Tribal boundaries are established around the natural preferences of the tribe. My friends didn’t need a formal policy to exclude a Kentuckian from our group. Our natural unconscious bias did that. Once policies are created around our prejudices, we develop practices to reinforce them. These practices become normative to the same degree that the motivating attitudes are invisible. Because of this, removing a tribal boundary marker requires more effort and dedication than establishing it in the first place. Hence, it took every bit of six decades to overcome the issue of segregation in the AG.

This could lead us to much self-congratulations, high-fives, and pats on the backs, but as we journey upstream, we realize that segregation is merely a symptom of other societal ills. What are those ills and have we addressed them as well? The one thing we learned from Brown vs Board of Education is that separate is inherently unequal. Segregation caused collateral harm. What are those harms and what should be done to address them?

The bigger question is: do we have the will to discover and to address these injustices? Or will we be paralyzed by fear of tribal recriminations? Or will we be like Thomas Zimmermann, and have the courage, not only to journey upstream, but to address the biblical injustices in a way that brings healing to all?